ERNEST HENRY WILSON - PIONEERING BOTANIST

1876 - 1930

1876 - 1930

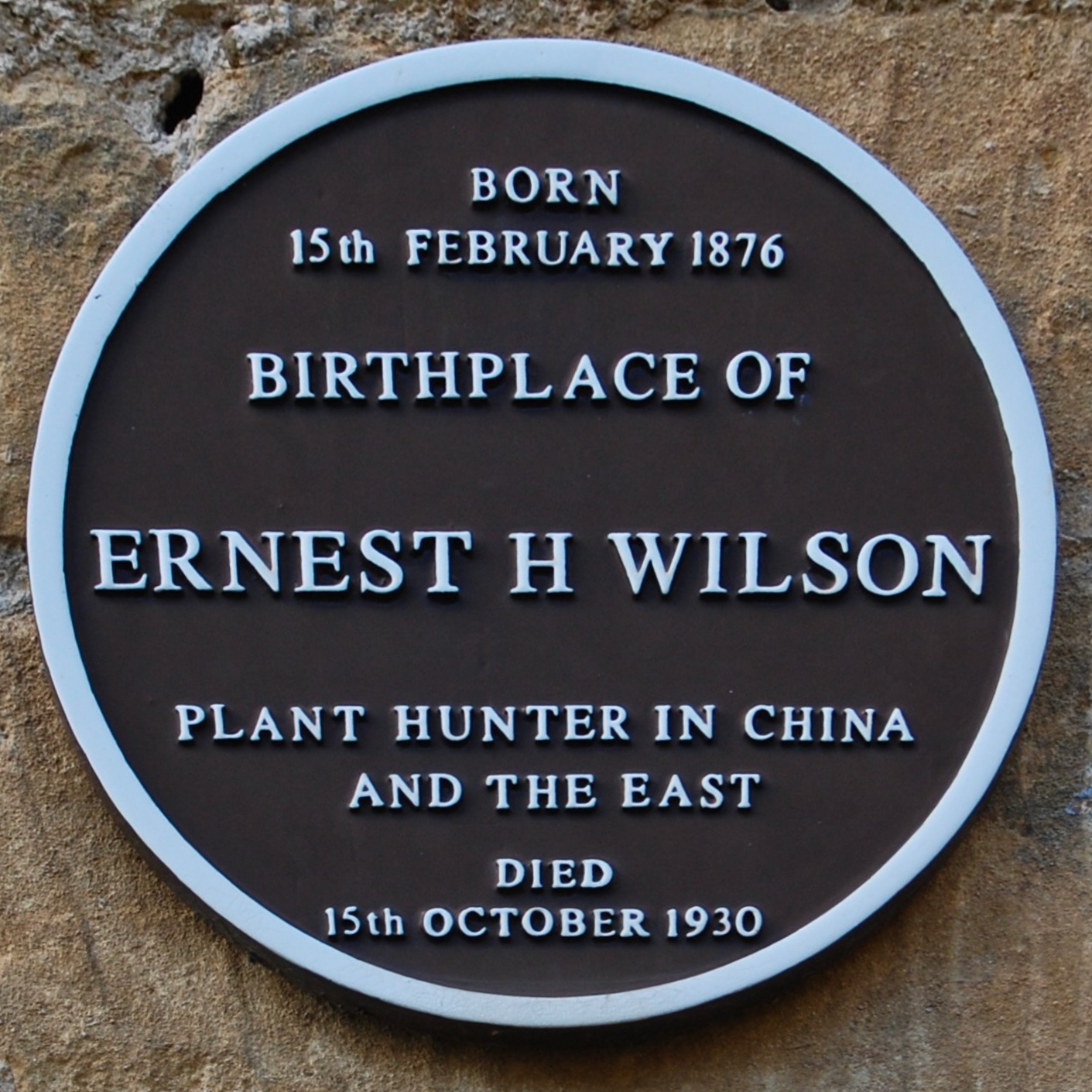

Ernest Henry Wilson (better known as E.H. Wilson) was born at Davies House on the upper side of the Lower High Street in Chipping Campden. The house is now marked by a plaque. When he was quite young the family moved to Monkspath, Shirley where he attended Shirley School. At the age of 13 he started work at Hewitt's Nurseries in Solihull, which was situated next to the railway station. The houses of Dorchester Road now stand on the site. Ernest moved to Birmingham Botanical Gardens when he was sixteen, then on to the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew.

It was while working there, in 1899, that he was recommended by the Director of Kew to go to China on a plant collecting expedition for the nursery firm of James Veitch and Sons of Chelsea. The expedition was to search for the source of the Handkerchief tree (Davidia incoluvata). On his way to China he stopped at the Arnold Arboretum in Boston with a letter of introduction to Director Charles Sprague Sargent to learn the best ways to ship plants and seeds safely.

Wilson made three further trips to China, and also visited Japan, Taiwan, India and South Africa, collecting plants for Veitch's and the Arnold Arboretum in America.

He was instrumental in discovering the Lilium regale, the large white trumpet type lily which graces many gardens, the yellow poppy meconopsis integrifolia and numerous new rhododendrons, roses and primulas.

Wilson became Director of the Arnold Arboretum in Boston, Massachusetts in 1927, quite an achievement at the age of 50.

Unfortunately Wilson and his wife were tragically killed in a road accident in Massachusetts just three years later in 1930.

In recognition of his services to horticulture Wilson received many awards including The Victoria Medal of Honour from the Royal Horticultural Society of London in 1912.

Wilson's Voyages of Discovery

In 1899, China was a dangerous place. Following the extended Opium Wars between Britain and the Qing dynasty, during which large numbers of Chinese and many Europeans were killed, some travellers in China adopted Chinese dress, but Wilson was never seen to be photographed in anything other than Western dress.

He travelled as light as possible, using the Chinese "inns" along his route rather than use tents. Wilson observed that the latter were something of a novelty in China and were likely to attract unwanted attention.

Wilson took dogs with him on all his expeditions to China. They provided him with companionship and were also used to recover game from thick cover such as Reeves pheasants which may seem somewhat excessive, but were intended as specimens for the Natural History Museum at Harvard, Cambridge, U.S.A.

Wilson hired local Chinese labour for his expeditions. He held his men in high regard and treated them well. In return they gave him loyalty and would journey for many days to join him on yet another expedition.

Much of Wilson's plant hunting was done on foot over some extremely difficult terrain. On his travels Wilson had to contend with almost impenetrable jungle, fever-filled swamps and all but impassable mountain ranges.

Wilson became an accomplished photographer and he always took the opportunity to photograph not only the flora but also scenes of Chinese village life.

Wilson always took two sedan chairs with him on expeditions. More often than not they were carried in pieces unused but the possession of such an item was an outward sign to any Chinese that he was a man of means - a person of importance and authority. The Chinese respected such shows of wealth and gave Wilson less unwanted attention than he might otherwise could have experienced.

Where possible, Wilson would use river transport which was much speedier than travel by foot and mule. However, the rivers often contained dangerous rapids strewn with boulders which could smash a tiny houseboat to matchwood. On one of Wilson's expeditions, one of his boats all but foundered and one of his men was drowned.

Wilson was always astonished by the fortitude of the Chinese peasants he met with on his travels. Goods of all types were more often than not transported by human “mules".

On his first trip to China, Wilson came across an unusual vine, growing in the locale of the British Treaty Port of Yichang on the Yangtze, which bore an edible fruit. Wilson introduced the plant into Britain and later the United States. The fruit was nicknamed "Wilson's Chinese Gooseberry". Today it is grown commercially in many countries including New Zealand and is now generally known as the "Kiwi Fruit”.

On his fourth expedition to China in 1910, Wilson was to collect bulbs of the beautiful "Lilium regale" (Regal Lily). Whilst negotiating a difficult mountain track, he was almost killed in a rock-slide and sustained a broken leg which soon became gangrenous. His men carried him for three days to the relative safety of a mission station at Chengdu. Here he underwent very painful surgery to his right leg, a procedure which left him with a permanent limp. Later Wilson often joked about this event in his life and would refer to his disability as his "lily limp”. Wilson always said that his ordeal under chloroform and ether was the hardest thing he ever had to endure in his life.

After his accident in 1910, Wilson became more or less desk-bound. However, his employers, the Arnold Arboretum of Boston, Massachusetts, knew that Wilson's forte was in fieldwork.

They therefore decided to send him on a less arduous expedition to the Far East. Here, he would visit the islands of Japan to collect plant material and make a record of the flora there, as well as make some side trips to Korea and Formosa.

As the work would not involve the “rough and tumble" of expeditions in China, Wilson would be allowed to take with him his wife Nellie, and daughter Muriel, from whom he had often been separated for years at a time. Wilson later wrote to his mother, "Everything is novel and interesting, especially to Nellie and Muriel and both are having the time of their lives. Having them with me makes it much pleasanter and infinitely less lonely for me”.

However, events in Europe were soon to alter what must have seemed like a holiday to the Wilson family. Now unable to return to England the Wilson family spent most of the war years in the Far East.

At the time of the First World War, Wilson was in Formosa (Taiwan), where he befriended "headhunters" from local tribes, together with a number of armed Japanese policeman sent along by the authorities for his protection.

Although his expeditions to Japan, Korea and Formosa did not present the difficulties of Western China, much of the terrain he encountered was rough and it must have been arduous work for a man with Wilson’s disability.

After the war, Wilson returned to Boston in 1919 and took up office at the Arnold Arboretum, where he served as Assistant Director for the next eight years. In 1920, Wilson departed on what was to be his last great trip, a two year "whistle-stop" tour of India, Africa, New Zealand, Tasmania and Australia. This was largely a public relations exercise on behalf of the Arnold Arboretum, America's foremost plant experimental station.

Life after exploring

On his return to America, Wilson "fell in love" with the motor car and he jokingly vowed that he would never walk anywhere else again. By now though, Wilson had only a few more years to live and spent much of that writing books and articles. The cars he owned were often used to transport himself and his photographic equipment around Massachusetts as he gathered material for his last book, Aristocrats of the Trees, (1930) which contains many photographs taken on such expeditions.

It must be regarded as one of the greatest ironies that a man who had endured so much on his many expeditions would lose his life on a suburban highway in 1930 at the wheel of one of his "much loved” motor cars. Another irony is that Wilson's wife, Nellie, so often apart from him in life, should join him in death. Their bodies were cremated in Boston and later interred in Mount Royal cemetery, Montreal, Canada.

The news of Wilson's death was met with shock and disbelief by all those that had known him. The Boston Globe summed up the nature of the man and his exploits in a short headline on its front page: "Tales of the Arabian Nights pale beside those of “Chinese" Wilson”.

Today his memory continues to live on in Chipping Campden. The complete collection of medals which were awarded to him can be seen in the Town Hall. Plants in the Memorial Garden grown from specimens he discovered from all over the world must surely be the best tribute and living memorial for one of the greatest botanists this country has ever known.